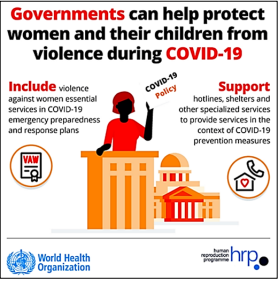

(Disponível em https://www.who.int/reproductive health/publications/covid-19-vaw-infographics/en/. Acessado em 01/08/2020.)

O cartaz anterior, divulgado pela Organização Mundial da

Saúde no contexto da atual pandemia, destaca o papel dos

governos em

‘The Complete Stories,’ by Clarice Lispector

By Terrence Rafferty

July 27, 2015

There’s a whiff of madness in the fiction of Clarice Lispector. The “Complete Stories” of the Brazilian writer, edited by Benjamin Moser and sensitively translated by Katrina Dodson, is a dangerous book to read quickly or casually because it’s so consistently delirious. Sentence by sentence, page by page, Lispector is exhilaratingly, arrestingly strange, but her perceptions come so fast, veer so wildly between the mundane and the metaphysical, that after a while you don’t know where you are, either in the book or in the world. So it’s best to approach her with some caution. For the ordinary reader — that is to say, for most of us — immersion in the teeming mind of Clarice Lispector can be an exhausting, even a deranging, experience, not to be undertaken lightly. (Pack food, water, a first aid kit and plenty of sunblock.)

Her stories are full of strange words, in strange combinations, and her “Complete Stories” is a remarkable book, proof that she was — in the company of Jorge Luis Borges, Juan Rulfo and her 19th-century countryman Machado de Assis — one of the true originals of Latin American literature.

THE COMPLETE STORIES

By Clarice Lispector

Edited by Benjamin Moser

Translated by Katrina Dodson

645 pp. New Directions. $28.95.

(Adaptado de https://www.nytimes.com/2015/08/02/books/review/the-completestories-by-clarice-lispector.html. Acessado em 21/07/20.)

No texto acima, o livro de Clarice Lispector recebe uma

crítica

Catherine Fletcher, Tue 4 Feb 2020

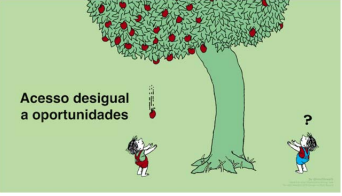

The decision by a UK University to close history, modern languages and politics degrees in favour of more “careerfocused” courses has been widely criticised. The problem lies in reducing university education to what sells to employers. A society – and a world – urgently needs people who have the education to think about big issues, which aren’t only scientific or technological: they’re also about the ways that people have made, and continue to make, decisions. The humanities matter. And it matters that students from all backgrounds have the opportunity to join in these world-changing discussions.

Roger Brown, Mon 10 Feb 2020

Catherine Fletcher is completely correct to warn about the damage that current policies are doing to the humanities. But her warning comes much too late. As I and other scholars have shown, the problem started with a government green paper which declared that the fundamental purpose of higher education was to serve the economy. Until we recover the idea that higher education is as much about the public good as anything else, we will never be able to sustain the humanities as an essential component of a balanced curriculum. Unfortunately, there is very little sign that this has been grasped by any of our current policymakers.

(Adaptado de www.theguardian.com/education/2020/feb/10/humanities-are-notthe-right-courses-to-cut. Acessado em 22/05/2019.)

Os textos acima concordam quanto à identificação de

um problema nos cursos universitários no Reino Unido,

mas divergem quanto

Sobre o texto “The best science images of the year: 2019 in

pictures”, considerando a imagem radiográfica que ele traz,

é correto dizer:

Injured ape

Nisha Gaind (Bureau chief, Europe). This X-ray shows a baby Sumatran orangutan (Pongo abelii) with a fractured arm. Conservation workers rescued the animal, named Brenda, from a village on the Indonesian island where she had reportedly been kept illegally as a pet. As editors, we see lots of photographs of conservation, but this image struck me for many reasons: the ‘humanness’ of Brenda’s shape, her innocence and the dedication of the conservation centre, which flew in a surgeon to operate on the animal.

(N. Gaind e E. Callaway. The best science images of the year: 2019 in

pictures. Nature, v. 576, n. 7787, p. 354–359, 16/12/2019.)

Robot priests can bless you, advise you, and even perform your funeral

By Sigal Samuel Updated Jan 13, 2020, 11:25am EST

A new priest named Mindar is holding forth at Kodaiji, a 400-year-old Buddhist temple in Kyoto, Japan. Like other clergy members, this priest can deliver sermons and move around to interface with worshippers. Mindar is a robot, designed to look like Kannon, the Buddhist deity of mercy, and cost $1 million.

As more religious communities begin to incorporate robotics — in some cases, AI-powered — questions arise about how technology could change our religious experiences. Traditionally, those experiences are valuable in part because they leave room for the spontaneous and surprising, the emotional and even the mystical. That could be lost if we mechanize them.

Another risk has to do with how an AI priest would handle ethical queries. Robots whose algorithms learn from previous data may nudge us toward decisions based on what people have done in the past, incrementally homogenizing answers and narrowing the scope of our spiritual imagination. One could argue, however, that risk also exists with human clergy, since the clergy is bounded too — there’s already a built-in nudging or limiting factor.

AI systems can be particularly problematic in that they often function as black boxes. We typically don’t know what sorts of biases are coded into them or what sorts of human nuance and context they’re failing to understand. A human priest who knows your broader context as a whole person may gather this and give you the right recommendation.

Human clergy members serve as the anchor for a community, bringing people together. They provide human contact, which is in danger of becoming a luxury good as we create robots to more cheaply do the work of people. Robots, notwithstanding, might be able to transcend some social divides, such as race and gender, to enhance community in a way that’s more liberating.

Ultimately, in religion as in other domains, robots and humans are perhaps best understood not as competitors but as collaborators. Each offers something the other lacks.