Os dados numéricos trazidos pelo infográfico têm o objetivo de

Leia o infográfico a seguir e responda à questão.

Leia o infográfico a seguir e responda à questão.

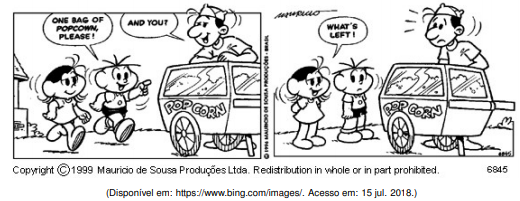

Leia a tirinha a seguir.

Na tirinha, o humor é evidenciado por meio

Em relação ao que se pode inferir do infográfico, considere as afirmativas a seguir.

I. Leitura e aritmética são consideradas habilidades necessárias para a vida e para o mercado de trabalho.

II. A questão da falta de habilidades atinge crianças, jovens e adultos.

III. Há um elevado número de crianças que não terminam o ensino primário.

IV. A quantidade de educadores é dado relevante para o enfrentamento dos problemas na Educação.

Assinale a alternativa correta.

Leia o infográfico a seguir e responda à questão.

De acordo com o infográfico, considere as afirmativas a seguir.

I. Os pobres e os marginalizados são maioria quando se trata de falta de habilidade de leitura e escrita.

II. Mais da metade dos analfabetos em idade adulta são mulheres.

III. 30% das crianças não completam o ensino primário em países desenvolvidos.

IV. 250 milhões de crianças frequentam a escola primária.

Assinale a alternativa correta.

Leia o infográfico a seguir e responda à questão.

Com relação às informações trazidas pelo texto, atribua V (verdadeiro) ou F (falso) às afirmativas a seguir.

( ) Um quinto das mulheres relatam ter sofrido algum tipo de violência no ano de 2017.

( ) A definição de violência restringe-se a tentativas de assassinato.

( ) Outras ações são desnecessárias já que o projeto está sendo bem sucedido.

( ) A violência no Estado do Espírito Santo vem aumentando desde 2005.

( ) O programa tem um papel pequeno no enfrentamento da violência contra a mulher

A obra Quarto de Despejo de Carolina Maria de Jesus é escrita na forma de diário, que se inicia em 15 de julho de 1955 e termina em 1º de janeiro de 1960.

Sobre essa forma, assinale a alternativa correta.

Em relação aos recursos linguístico-semânticos do texto, relacione as colunas de modo a identificar a função dos termos em destaque.

(I) Until this changes, Gaviorno and her colleagues will have their work cut out.

(II) From the female lawyer who asks for something from the judge and gets it because she is pretty, to the woman who is murdered by her husband. . .

(III) Everyone arrested for violence against women must attend an introductory lecture.

(IV) “You can’t just wait with your arms folded while the justice system takes its time to do something,”

(V) Group sessions are run like an AA group.

(A) Demonstra obrigatoriedade de uma ação.

(B) Aponta “limite” de algo.

(C) Demonstra que duas ações acontecem ao mesmo tempo.

(D) Aponta “origem e limite” de algo.

(E) Compara duas ideias.

Assinale a alternativa que contém a associação correta.

Leia o poema a seguir.

não vai dar tempo

de viver outra vida

posso perder o trem

pegar a viagem errada

ficar parada

não muda nada

também

pode nunca chegar

a passagem de volta

e meia vamos dar

(RUIZ S., Alice. Dois em um. São Paulo: Iluminuras, 2018. p. 171.)

Com base no poema, considere as afirmativas a seguir.

I. O sujeito lírico defende uma concepção de amor avessa a aventuras e ímpetos.

II. O sujeito lírico deposita ênfase na ideia de aceleração, segundo a qual, é preciso fazer tudo funcionar satisfatoriamente no presente.

III. O terceiro e o quarto versos apontam imagens que remetem a riscos e insucessos.

IV. O sujeito lírico no feminino assume a condição de uma mulher que rejeita a passividade.

Assinale a alternativa correta.

Quanto à relação entre o conto “Os laços de família” e os demais contos do livro, assinale a alternativa correta.

Leia o poema a seguir.

tua mão

no meu seio

sim não

não sim

não é assim

que se mede

um coração

(RUIZ S., Alice. Dois em um. São Paulo: Iluminuras, 2018. p. 30.)

Sobre o poema, considere as afirmativas a seguir.

I. A referência ao corpo significa uma predisposição do sujeito lírico para o amor físico.

II. O terceiro e o quarto versos apontam para a ideia de dúvida quanto ao consentimento da carícia.

III. O quinto verso, apesar de proporcionar jogo de palavras com o verso anterior, representa um modo diferente de interpretar o gesto da mão no seio.

IV. Nos dois versos finais, a ideia de medir o coração é utilizada em linguagem figurada para remeter à avaliação de sentimentos.

Assinale a alternativa correta.

A dor representava o remorso sentido em Catarina, que deixou de aproveitar a visita da mãe para lhe contar que estava na iminência de se separar do marido.

Leia o trecho a seguir, extraído do conto “Preciosidade”, do livro Laços de família, e responda à questão.

Não, ela não estava sozinha. Com os olhos franzidos pela incredulidade, no fim longínquo de sua rua, de dentro do vapor, viu dois homens. Dois rapazes vindo. Olhou ao redor como se pudesse ter errado de rua ou de cidade. Mas errara os minutos: saíra de casa antes que a estrela e dois homens tivessem tempo de sumir. Seu coração se espantou.

O primeiro impulso, diante de seu erro, foi o de refazer para trás os passos dados e entrar em casa até que eles passassem: “Eles vão olhar para mim, eu sei, não há mais ninguém para eles olharem e eles vão me olhar muito!” Mas como voltar e fugir, se nascera para a dificuldade. Se toda a sua lenta preparação tinha o destino ignorado a que ela, por culto, tinha que aderir. Como recuar, e depois nunca esquecer a vergonha de ter esperado em miséria atrás de uma porta?

(LISPECTOR, C. Laços de família. 11. ed. Rio de Janeiro: José Olympio, 1979. p. 101-102.)

Leia a tirinha a seguir e responda à questão.