7474f854-b8

CEDERJ 2015 - Inglês - Interpretação de texto | Reading comprehension

According to the text, friends who are always in

trouble because they do not follow our advice should be

treated with

According to the text, friends who are always in

trouble because they do not follow our advice should be

treated with

Why don’t we take our own advice?

Oliver Burkeman

“Why is it so hard to take your own advice?” the psychology writer Melissa Dahl asked in a New York magazine essay some months ago, and the question’s been bugging me ever since. I have the arrogance to imagine that if you followed some of the suggestions made each week in this column, you might be a little happier or more productive, with a little less relationship drama, a little more inner calm. (From my email inbox, I know this happens at least occasionally.) But were you to infer from this that I follow such advice flawlessly myself, you’d be mistaken. When friends mention their difficulties with partners or bosses, Dahl wrote, she always tells them to talk to the person involved. Just say something! “And probably, this is good advice,” she mused. “I wouldn’t know, as it’s something I rarely do myself.” I can understand. I suspect most of us can. As the old wisecrack has it: “Take my advice – I’m not using it.”

The cynical take on this is that we ignore our own advice because it’s rubbish: we give it to seem wise, when in fact it’s nonsense. (All advice to “try harder” or “snap out of it” or “look on the bright side” fall into this category: if the recipient could do so, he or she already would have, without your so-called help.)

But a more interesting notion is that the advice is often good – yet something prevents us applying it to ourselves. One such obstacle is simply too much information: inside our own heads, we have access to all manner of details, making us believe that this relationship problem, this job dilemma, is special, so the advice doesn’t apply. Dahl cites work by the psychologist Dan Ariely, showing that when a friend gets a serious medical diagnosis, most people would urge them to get a second opinion. But were it to happen to themselves, they’d be more likely not to do so, for fear of offending their doctor. The fear of offence is something you’d think of only in your own case – and it’s totally unhelpful.

But there’s another big reason I don’t follow my own advice: the huge gulf between grasping something intellectually and really feeling it in your bones. For example, it was years ago that I first encountered the insight that anxiety and insecurity aren’t reduced by trying to exert more control over the world; in fact, that usually makes them worse. I know this. But apparently I have to keep learning it, over and over. Its correctness isn’t sufficient for it to get into my brain once and for all; that takes repeated experience. As a result, I continue to “suddenly realise” things I already wrote an entire book about.

If nothing else, this should be a caution against getting too frustrated with that one friend of yours who keeps getting into the same kind of pickle, time and again, deaf to the obviously good advice that everyone keeps offering. You know the type. We’ve all got a friend like that. The scary thought is that, for some of your friends, it’s probably you.

Adapted from http://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2015/sep/11/ taking-your-own-advice-oliver-burkeman. Accessed on: 22 out. 2015.

Glossary

Oliver Burkeman

“Why is it so hard to take your own advice?” the psychology writer Melissa Dahl asked in a New York magazine essay some months ago, and the question’s been bugging me ever since. I have the arrogance to imagine that if you followed some of the suggestions made each week in this column, you might be a little happier or more productive, with a little less relationship drama, a little more inner calm. (From my email inbox, I know this happens at least occasionally.) But were you to infer from this that I follow such advice flawlessly myself, you’d be mistaken. When friends mention their difficulties with partners or bosses, Dahl wrote, she always tells them to talk to the person involved. Just say something! “And probably, this is good advice,” she mused. “I wouldn’t know, as it’s something I rarely do myself.” I can understand. I suspect most of us can. As the old wisecrack has it: “Take my advice – I’m not using it.”

The cynical take on this is that we ignore our own advice because it’s rubbish: we give it to seem wise, when in fact it’s nonsense. (All advice to “try harder” or “snap out of it” or “look on the bright side” fall into this category: if the recipient could do so, he or she already would have, without your so-called help.)

But a more interesting notion is that the advice is often good – yet something prevents us applying it to ourselves. One such obstacle is simply too much information: inside our own heads, we have access to all manner of details, making us believe that this relationship problem, this job dilemma, is special, so the advice doesn’t apply. Dahl cites work by the psychologist Dan Ariely, showing that when a friend gets a serious medical diagnosis, most people would urge them to get a second opinion. But were it to happen to themselves, they’d be more likely not to do so, for fear of offending their doctor. The fear of offence is something you’d think of only in your own case – and it’s totally unhelpful.

But there’s another big reason I don’t follow my own advice: the huge gulf between grasping something intellectually and really feeling it in your bones. For example, it was years ago that I first encountered the insight that anxiety and insecurity aren’t reduced by trying to exert more control over the world; in fact, that usually makes them worse. I know this. But apparently I have to keep learning it, over and over. Its correctness isn’t sufficient for it to get into my brain once and for all; that takes repeated experience. As a result, I continue to “suddenly realise” things I already wrote an entire book about.

If nothing else, this should be a caution against getting too frustrated with that one friend of yours who keeps getting into the same kind of pickle, time and again, deaf to the obviously good advice that everyone keeps offering. You know the type. We’ve all got a friend like that. The scary thought is that, for some of your friends, it’s probably you.

Adapted from http://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2015/sep/11/ taking-your-own-advice-oliver-burkeman. Accessed on: 22 out. 2015.

Glossary

advice: conselho; to bug: incomodar; to infer: concluir;

flawlessly: perfeitamente; to muse: meditar; wisecrack:

espertinho; cynical: cínico, pessimista; rubbish:

besteira; to urge: insistir; gulf: distância; exert: exercer;

pickle: encrenca

A

fear.

B

frustration.

C

tolerance.

D

indifference.

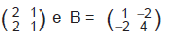

é a matriz nula de ordem 2.

é a matriz nula de ordem 2. .

.